Will a Dry Ice Shortage Impact Your Sanitation Program?

Used to maintain the super-cold temperatures necessary for the transport of Covid-19 vaccines and with vaccines being rolled out over the next few months, demand for dry ice is expected to increase dramatically. This has prompted the question of whether a potential shortage could impact the food manufacturing industry.

Food manufacturers traditionally use dry ice in a number of ways, including to rapidly cool meat after processing and in preparation for shipping, to preserve dairy cultures for shipment to cheesemakers and other dairy processors, and to help control fermentation of yeast.

Recently, dry ice cleaning has even become a preferred method for sanitation in food manufacturing facilities due to its many benefits and as departments have adapted to new cleaning solutions to help control overhead costs. But with the industry potentially facing a dry ice shortage, more traditional methods of cleaning may have to be used.

How Do I Choose an Alternative Cleaning Solution?

When evaluating and selecting an alternative cleaning solution, there are key questions you and your team should consider.

Should I Opt for Wet Cleaning Instead of Dry?

I recommend avoiding wet cleaning when possible. While the use of water may be necessary in certain high-risk facilities like meat processing plants, sites dealing with low water activity foods like baked goods, snacks, and certain confections should avoid or minimize water usage during cleaning. In these dry ingredient production zones, any moisture or condensation remaining on equipment or surfaces can act as a medium for microbial growth, and thus create a significant food safety concern. Dry cleaning methods like using scrapers, sweeping, and vacuuming are generally employed in these environments.

Dry Cleaning Methods and Tools

If you choose to maintain a dry cleaning process, there are a number of methods and tools that can be used in place of dry ice cleaning, including:

- Manual cleaning with hand tools

- Vacuuming

- Product flushes

- Sanitizer wipe downs

- Sanitizer applications (with minimal water)

- Limited compressed air (In addition to spreading debris to other areas and prompting cleaning in other areas, this could create aerosols and disperse virus through the air, so should be a last resort option)

Seven Steps of Dry Cleaning

If you were using dry ice cleaning, these are steps that should have already been in place but can serve as a good refresher when changing to a different process:

- Sanitation preparation

- Secure and disassemble equipment

- Dry clean from the top of the equipment down. Should you have any parts to separately wet clean, ensure they are completely dry before returning

- Detail clean from the top down

- Post inspection and re-clean if necessary

- Pre-operation inspection, cleaning verification and reassembly

- Sanitize

Should you implement a new process, keep in mind best practices for doing so:

- Engage all personnel. Maintaining quality in a food processing facility is everybody’s job, and an essential component of quality is sanitation. Even the people who do not participate in the sanitation process should have an awareness of its importance and understand how their actions can have an impact. This starts with leadership ensuring that sanitation teams have adequate resources to perform the work, including time, training, employees, equipment, sanitizers, and potable water.

- Use the right types of sanitation tools for the task. Using the wrong tool might damage the equipment and result in ineffective cleaning. Generally, soft-bristled brushes are used for sweeping dry, fine powdery soils from a surface. For larger and moist debris, medium-bristled brushes are effective. Stiffer bristled brushes can be used to scrub stuck-on dirt from a surface with water and cleaning agents.

- Develop written SSOP’s. Every step in the cleaning and sanitation process has a SSOP, and they exist for a reason. Have documentation readily available for sanitation crews, especially for processes that do not happen frequently. SSOPs should include information such as:

- Safety Equipment needed to perform the cleaning task

- Types of tools needed for cleaning and dismantling of equipment

- How to dismantle equipment

- Application procedures for specific equipment

- Chemical concentrations for cleaners and sanitizers of needed

- Contact times for sanitizers

- Allocate a cleaning schedule for every surface or area in the facility. Along with a Master Cleaning Schedule, it is essential to have a set of cleaning implements to cover each significant area within a food plant. For example, a condensation squeegee with long extension handle can remove water droplets from high-reaching ceiling panels; ergonomic, angled brooms can remove dirt from undersides of equipment; pipe brushes or narrow utility brushes can perform detailed cleaning of pipes or nooks and crannies within equipment; and a good scrubbing brush can clean a wide surface such as a tabletop counter.

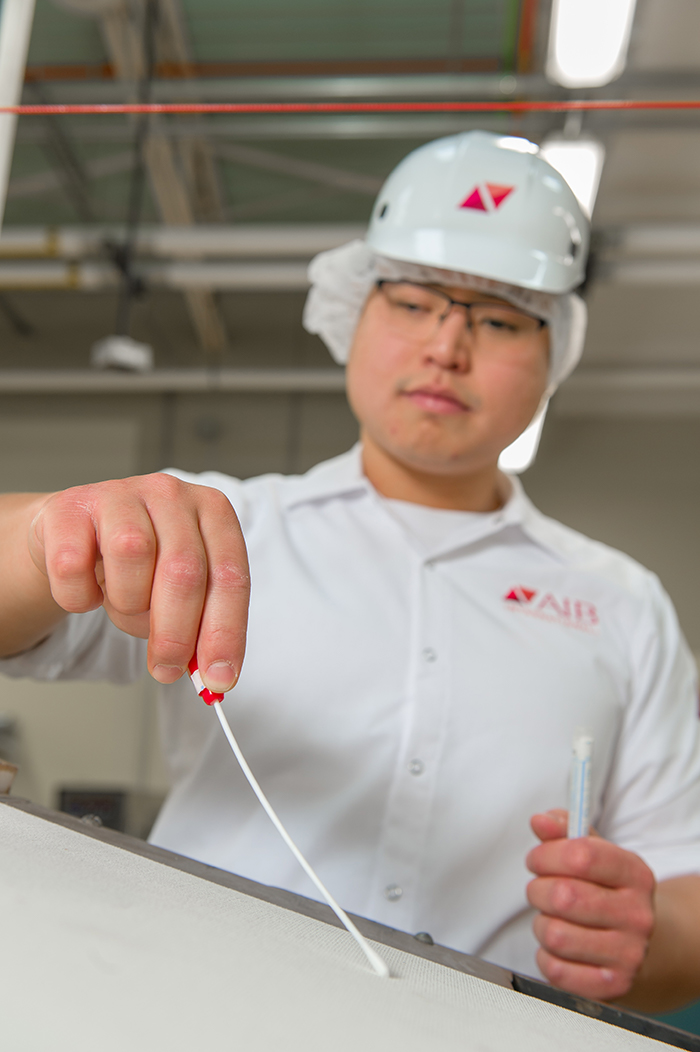

- Validation and Verification. Validation should be conducted through both visual inspection and protein swabs. Additionally, FDA recommends that all cleaning and sanitizing procedures be regularly monitored for effectiveness, through pre-operational inspections or audits and microbial sampling of the environment and food-contact surfaces. Verification criteria should include that no visible residue be present and micro counts be within acceptable limits.

Foreseeing a possible dry ice shortage and with some facilities having to opt for more traditional sanitation cleaning programs, it is critical to ensure that yours is effective. Whichever you choose, it should be fully defined with your plant’s specifications, cleaning schedule, and with assigned responsibilities detailed in written SSOPs. Staff then should be trained, not only on the SSOPs, but on chemical safety and effectiveness, and the importance of the final validation and corrective action for any remaining allergens, soils, or micros. Having these steps in place will ensure a smooth transition from a dry ice cleaning program to an effective alternative.

Foreseeing a possible dry ice shortage and with some facilities having to opt for more traditional sanitation cleaning programs, it is critical to ensure that yours is effective. Whichever you choose, it should be fully defined with your plant’s specifications, cleaning schedule, and with assigned responsibilities detailed in written SSOPs. Staff then should be trained, not only on the SSOPs, but on chemical safety and effectiveness, and the importance of the final validation and corrective action for any remaining allergens, soils, or micros. Having these steps in place will ensure a smooth transition from a dry ice cleaning program to an effective alternative.

Should you have any questions or need anything further, please contact us at info@aibinternational.com.

Scott Bowman

This blog was authored by Scott Bowman, Food Safety Professional, AIB International. Bowman has been in the industry for more than 29 years, holding a variety of positions, including Food Safety Manager, Sanitation Manager, and Plant Manager. He is a graduate of AIB International’s residence courses in The Science of Baking and Food Safety and Sanitation. He also holds AIB certifications in HACCP, Principles of Food Plant Auditing, Food Defense Coordinator, PCQI, Hygiene and Sanitation, and Fundamentals of Baking.

This blog was authored by Scott Bowman, Food Safety Professional, AIB International. Bowman has been in the industry for more than 29 years, holding a variety of positions, including Food Safety Manager, Sanitation Manager, and Plant Manager. He is a graduate of AIB International’s residence courses in The Science of Baking and Food Safety and Sanitation. He also holds AIB certifications in HACCP, Principles of Food Plant Auditing, Food Defense Coordinator, PCQI, Hygiene and Sanitation, and Fundamentals of Baking.